The official European Union Anthem is the final choral movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, based on Schiller’s poem ‘An die Freude’ (‘Ode to Joy’, although the original version apparently had ‘freedom’ instead of ‘joy,’ which Schiller later deleted as too hot a political potato for his day).

Beethoven starts the movement with these words of his own:

- O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!

- Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen,

- und freudenvollere.

- Oh friends, not these sounds!

- Let us instead strike up more pleasing

- and more joyful ones!

After the Eurozone’s marathon reenactment of Buñuel’s film The Exterminating Angel, the Brussels Crucifixion of Greek PM Alexis Tsipras, and the Guns of Navarone, political discourse around the world has taken a sharp turn in the direction of recrimination, vituperation, polarization, slander and hysteria. On the one hand we have the Twitter hasttag #Thisisacoup denouncing the third Greek bailout terms, on the other we have a touchy nationalistic pushback in establishment German circles, media, and public opinion, as reported for instance in Jacob Soll’s recent NYT op-ed (also see previous post). And European Council president Donald Tusk “had been unsettled by the bitter recriminations that have characterised the contentious six-month Greek negotiations, particularly the anti-EU and anti-German sentiment that he believes has become part of mainstream political discourse,” reports the Financial Times.

On July 12, Paul Krugman in his NYT blog came out strongly in support of the #Thisisacoup camp:

This goes beyond harsh into pure vindictiveness, complete destruction of national sovereignty, and no hope of relief…

Who will ever trust Germany’s good intentions after this? …

The European project — a project I have always praised and supported — has just been dealt a terrible, perhaps fatal blow. And whatever you think of Syriza, or Greece, it wasn’t the Greeks who did it.

Official German circles and their lackeys (I hate to use such a loaded word from communist propaganda days, but it really seems appropriate) did not waste any time in riposting with a character assassination, by Nikolaus Piper in the Süddeutsche Zeitung on July 13. Under the section link “Paul Krugman--Economist foaming at the mouth,” Piper describes Krugman as joining the hashtag campaign of “Germany haters” (Germany being only one of his many pet targets, but currently his favorite), a “hyper-Keynesian” who thinks that new debt, low interest rates and government spending are always the answer to all problems, and that austerity is always false. He insinuates that Krugman’s Nobel Prize for his work in trade theory (actually trade and economic geography) is a questionable qualification for him to pontificate about fiscal (actually macroeconomic) policy while he blithely ignores facts, but Piper fails to mention Krugman’s work on exchange rates and currency crises and his publications on macro policy in a liquidity trap (e.g., Japan in the 90s) and, indeed, bailouts vs. write-downs. He ends with a recital of obscure Baltic politicians and playwrights with even lesser economic qualifications who have also felt an urgent need to defame Krugman. In other words, this is a complete hatchet job based on willful ignorance of the background of someone eminently qualified to comment on the Greek debt crisis (whether you agree with him or not), certainly light-years more qualified than Piper himself (who we are told on his SZ profile has written an award-winning children’s book on economics, among other things). The only invectives missing are “Keynesian running dog” and, of course, “spearhead of the world Jewish conspiracy against Germany,” but then, the Süddeutsche Zeitung is an honorable newspaper and has a reputation to uphold as a liberal paper of record that even republishes excerpts from the New York Times once a week. Strangely enough, the very same Nikolaus Piper conducted a rather favorable interview with Krugman in 2010, praising (if somewhat tongue-in-cheek) the very hang to polemic he now so roundly denounces in him. Is he not only a lackey of the German finance ministry but also suffering from unrequited love?

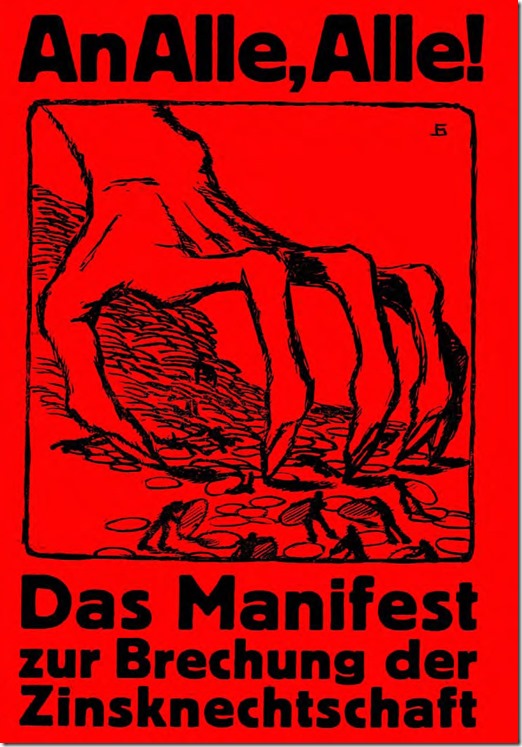

Is the hitherto respectable Süddeutsche Zeitung in danger of becoming the new Der Stürmer?

Now, anyone who follows Krugman’s blog and columns knows that he is

-

-

certainly not someone who “thinks that new debt, low interest rates and government spending are always the answer to all problems,” as a careful reading of his blogs would have made clear (e.g., his recent blog on Canada’s experience with austerity and why it differs from Greece’s).

That Piper might be part of an orchestrated campaign here (presumably by the German finance ministry, but of course I’m just speculating), comes out in Friday’s interview with German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble in Der Spiegel:

SPIEGEL: The American economist Paul Krugman has a clear position on that. The new aid program for Greece, he wrote in a recent column [actually in his blog, GS] in the New York Times, is "pure vindictiveness" and a "complete destruction of national sovereignty." Do you share his view?

Schäuble: Krugman is a prominent economist who won a Nobel Prize for his trade theory. But he has no idea about the architecture and foundation of the European currency union. In contrast to the United States, there is no central government in Europe and all 19 members of the euro zone must come to an agreement. It appears Mr. Krugman is unaware of that.

Schäuble thus repeats Piper’s mischaracterization of Krugman’s Nobel award and the insinuation that he is not qualified to judge these issues. Whether Piper is reading from Schäuble’s playbook, or vice versa, is hard to say, but this cannot be a coincidence. Would Schäuble’s perusing Krugman’s seminal 1988 paper “Financing vs. Forgiving a Debt Overhang” (Journal of Development Economics 29: 253-268) change his opinion about Krugman’s qualifications to comment on the Greek debt crisis in any way (on the unlikely assumption that Dr. Schäuble could even make heads or tails of it)?

And that Krugman might be oblivious of the cumbersome governance structure of the Eurozone also seems highly unlikely, besides being largely irrelevant. After all, who in the world today isn’t painfully aware of this deficiency after being subjugated to this excruciating five-year reenactment of The Exterminating Angel?

But we needn't take the word of a benighted American to judge whether there isn’t some justification in the #Thisisacoup accusations. Paul De Grauwe, former member of the Belgian Parliament, emeritus professor at the Catholic University of Leuven, currently professor at the London School of Economics, and one of the world’s leading experts on currency zones, is someone no-one could accuse of being unacquainted with the Eurozone’s architecture (or being a foaming-at-the-mouth “hyper-Keynesian,” for that matter). Yet in his blog on June 17, two weeks before the Guns of Navarone were fired or #Thisisacoup took off, he wrote:

All this teaches us two lessons. First, the objectives of the creditor nations, including the ECB, that today add tough conditions for their liquidity support is not to make Greece solvent but to punish it for misbehavior. … But it is precisely the desire to punish Greece by imposing additional austerity that makes it so difficult for Greece to start growing again and to extricate itself from the bad equilibrium.

A second lesson concerns the credibility of the future use of OMT. It clearly appears from the Greek experience that the willingness of the ECB to use the OMT program is very circumscribed. It is circumscribed by the ECB’s desire to solve a moral hazard problem … Behind the gloves of OMT is hidden a big stick. It is doubtful that future governments that experience payment difficulties will accept to be beaten up first before they can enjoy the OMT liquidity support. [my emphases]

Thus De Grauwe only lends further support to Krugman’s “this goes beyond harsh into pure vindictiveness, complete destruction of national sovereignty, and no hope of relief” critique, well before one could even speak of a “coup.”

Why is the German finance minister so sensitive to these criticisms that he seems almost overeager to resurrect the role of the “ugly German” (in the words of one German opposition parliamentarian)? The Oxford macroeconomist Simon Wren-Lewis has a plausible answer (and it’s not that Dr. Schäuble is a covert Nazi or auditioning for the role of Dr. Strangelove):

What is driving Germany’s desperate need to rid itself of the Greek problem?

One possible answer is that Germany finds the truth about Greece too upsetting, too challenging. This is because since 2010 Greece has done most of what the Troika asked of it. In particular, changes in its government’s underlying primary budget balance (i.e. the degree of austerity enacted) have been greater, by a long distance, than any other European economy. For many outside Germany what has happened to Greece as a result is hardly surprising: austerity is contractionary, and austerity on steroids is ruinous. Yet Germany is a country where the ideas of Keynes, and therefore mainstream macroeconomics in the rest of the world, are considered profoundly wrong and are described as ‘Anglo-Saxon economics’. Greece then becomes a kind of experiment to see which is right: the German view, or ‘Anglo-Saxon economics’.

The results of the experiment are not to Germany’s liking. Just as ‘Anglo-Saxon economics’ would have predicted, the results for Greece under the Troika have been a disaster. After dutifully taking the medicine for years, and seeing the collapse of their economy, finally the Greek people could take no more. Confronting this reality has been too much for Germany. So instead it has created its fantasy, a fantasy that allows it to cast its failed experiment to one side, blaming the character of the patient.

Wren-Lewis fails to mention that the Merkel government is also being very much driven, like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, by the public opinion it whipped up in the past about “those lazy Greeks,” and by the rise of Germany’s own anti-Euro and xenophobic movements like Alternative für Deutschland and Pegida.

Paul Krugman, as the most visible, vocal and dangerous (what with his flashy Nobel Prize) exponent of this ‘Anglo-Saxon economics’ (read ‘hyper-Keynesianism’), is the obvious policy-wonk Prügelknabe (read ‘whipping boy’) for so many reasons I cannot even begin to enumerate them here. One is perfectly within one’s rights to disagree with him, but then one should marshal legitimate arguments rather than revert to a sorry tradition of character assassination and defamation.

PS: You might be wondering what ‘Die Schonzeit ist vorbei’ is doing in the title of this post. I hesitated to use this very loaded German expression in this context, but will go out on a limb anyway. ‘Die Schonzeit ist vorbei’ (literal translation: ‘the no-hunting-season is over’, or more figuratively, ‘the hunting season has now been reopened’) is an expression attributed to the Frankfurt theater manager Günther Rühle to justify the 1986 staging of film and drama enfant terrible Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s play “Der Müll, die Stadt und der Tod” (although German courts later ruled that it would be inadmissible to attribute it to him, but then, we know how consistently German courts have ruled on touchy historical issues). The Jewish community in Frankfurt claimed that the play revived classical anti-Semitic stereotypes such had been used in the notorious Nazi propaganda film Jüd Süß, and that this transgression overruled the constitutional freedom of artistic expression.

While the campaign against Krugman does seem to have aspects of ‘reopening the hunting season,’ the perpetrators have been very careful to avoid any overt anti-Semitism (it is of course no secret that Krugman is Jewish). However, anyone intimately familiar with German sensitivities cannot help but recognize that Piper’s article is skating dangerously close to this kind of historical stereotyping, particularly by using the term “Hasskampagne gegen Deutschland” (“hate campaign against Germany”). I won’t even speculate on who is responsible for the Stürmer-like “Volkswirt mit Schaum vor dem Mund” (“economist foaming at the mouth”), which was carefully placed outside the body of Piper’s article (and thus cannot be directly attributed to him) but in a prominent position on the webpage, and appears as the article’s actual title—which it is not—in Google searches.